Race for Doggett's Coat & Badge: A Thames Institution Since 1715

On a stormy summer night in 1715, Irish comedian and stage manager Thomas Doggett needed a lift home from the Swann Tavern in London. He regularly used water taxis operated by local watermen to transport him along the River Thames to Chelsea, but on this particular night the weather was so foul that most men refused. But a young waterman, just free of his seven-year Company of Watermen and Lightermen apprenticeship offered his services, for which Doggett paid him well. That night, his idea was born to create a wager testing the sculling and "watermanship" abilities of newly qualified Thames watermen.

In commemoration of King George I's accession to the throne, Doggett founded the Race for Doggett's Coat and Badge (originally known as the Brunswick Coat and Badge Wager). On July 31, 1715, he placed a placard on London Bridge that read:

“This (Aug. 1, 1715) being the day of His Majesty’s happy accession to the throne there will be given by Mr. Doggett an orange color livery with a badge representing Liberty to the be rowed for by six watermen that are out of their time within the year past. They are to row from London Bridge to Chelsea. It will be continued annually on the same day for ever.”

More than 300 years later, the Race for Doggett's Coat & Badge through the heart of London is Britain's oldest rowing race and claims to be the oldest continuously run sporting event in the world. It continues to draw competitors keen to take home the namesake prizes, add their names to the roster of winners, and become a part of the Doggett legacy.

The Coat and the Badge

The coat was orange to "the immortal memory of William III who delivered Great Britain from slavery, poverty, and arbitrary power and bequeathed us the invaluable blessing which we now enjoy, a Protestant King.”

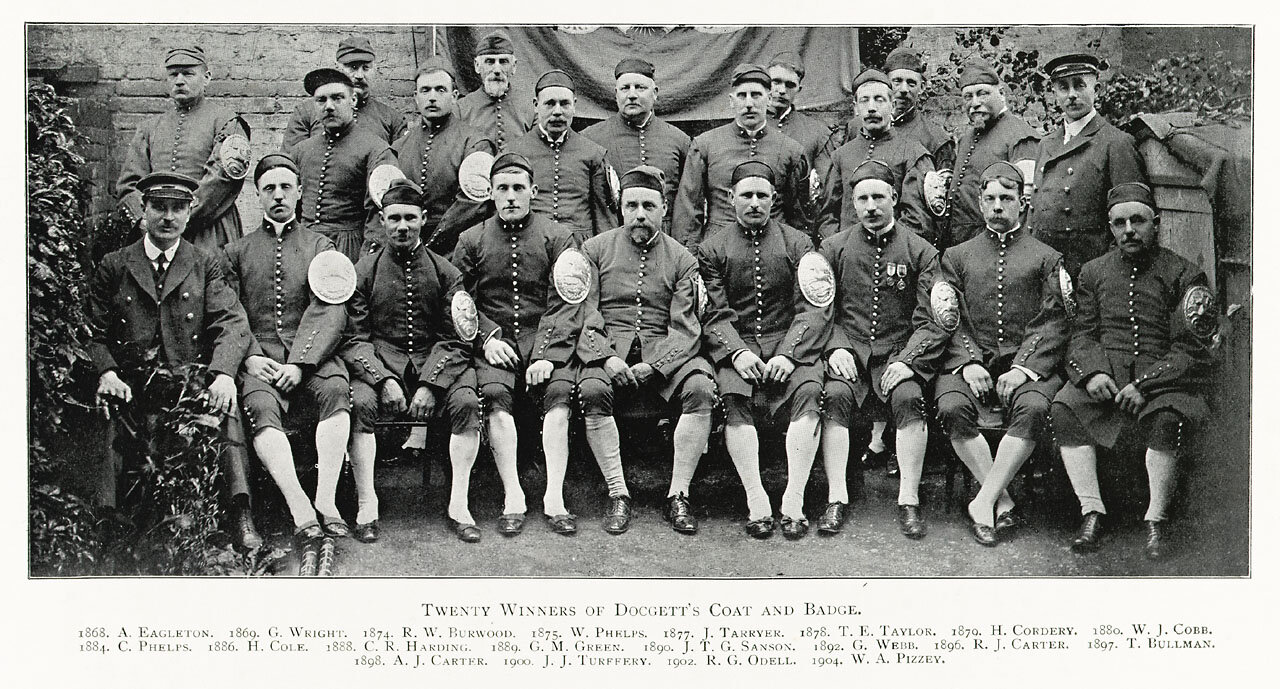

The Badge – the size of a salad plate and affixed to the left sleeve of the Coat – includes the word “Liberty” on a scroll around the “wild horse of the coat of arms of the house of Hanover” and the words “The Gift of Thomas Doggett, the late Comedian,” on another scroll underneath.

In addition to the orange-red tunic and large badge, winners of the race wear a livery complete with red cap, white stockings, and buckled shoes. (Liveries are a special form of dress to denote status of belonging to a trade in London.)

The Course

Since 1715, participants have plied the same 7,400m stretch of the Thames from London Bridge to the Cadogan Pier in Chelsea (see interactive map), where Doggett had a home. Back then, London Bridge was the only bridge in London, but today the race passes under 11 bridges on a course that is not – unlike most other race courses – closed to traffic. Rowers deal with turbulence around the bridges, and have to navigate a river cluttered with and cargo and passenger vessels.

Course map circa 1745.

In 1866, heavy steamboat traffic and concerns about boats being swamped led to a proposal to move the course farther up river, possibly between Putney and Mortlake.

Rowed against the tide until 1873 in four-passenger wherries, the race could take more than two hours to complete. Then it was decided to row the course with the in-coming tide in modern sculls and the overall times dropped dramatically, down to 25-30 minutes. The course record of 23:22 was set in 1973 – and still stands today – by Bobby Prentice, who went on to become the Bargemaster to the Fishmonger's Company and Upper Warden of the Company of Watermen and Lightermen.

Despite its long history and a course that passes through prime tourist territory, the race "draws only occasional waves from the banks of the river... [and] is considered a curious anachronism if it is considered at all," according to a 2012 New York Times article.

Participants

From the beginning, participation was restricted to young apprentices at Watermen's Hall, where they learned the watermen's trade. An apprenticeship in 1715 was a seven-year commitment, and company bylaws clarified that apprentices were "indentured" to a master or mistress and were "not to be employed in any other business," or "to make any advantage of his own labour for his own benefit, or to receive the profits thereof to his own use."

No apprentice was "free" until they had served seven years, and it was during their first year of freedom that a waterman was allowed to row for the coat and badge. The opportunity to race was a source of pride for waterman who wanted to demonstrate an ability to move goods and passengers the fastest.

In 1715 there were nearly 50,000 watermen on the Thames, and just six were selected by lottery each year to race, effectively giving them each just one attempt at the course. This custom remained in place until 1988 when it was recognized that fewer young men were apprenticing and the pool of eligible participants was dwindling. The rules were relaxed to give unsuccessful competitors permission to compete again in their second or third years of freedom, as long as they were no older than 26 on race day.

The participants are nearly always men, but in 1992 Claire Burran – sister of 1988 winner Glen Hayes – became the first woman to compete, and finished third.

Boats

The four-passenger wherries were large, every day work boats, so waterman began to remove bottom boards and extraneous items to lighten the load. But this early form of customization wasn't affordable for all potential participants and put poorer watermen at a disadvantage. New rules and regulations in 1769 stipulated all boats had to be full-size licensed wherries examined and approved by the Fishmonger's Company, which supplied the boats for many years.

Over time, wherries fell out of fashion, and watermen began to use "old fashioned boats" with wooden "wings." Then boat designs got narrower and incorporated wooden outriggers. They were very unstable though, and in the choppy Thames, these outriggers were often overtopped making blade work extremely challenging.

Public records of wagers show that in 1864 apparently an 8-oared and 10-oared cutter were raced. And four years later a newspaper reported that "the fragile craft now rowed in cannot enter into a bumping match with steamers."

The start of the race, 1906.

In February 1907, all restrictions were removed as to the style and build of the boat.

Today, WinTec/OarSport supports the race, and provides all competitors with shells that offer a unique self-bailing system to help handle the rough and turbulent Thames.

Below the Surface: More History

Thomas Doggett funded, organized, and managed the race each year until his death in 1721. In his will he clearly directed that his "executors shall forthwith by and out of my personal estate purchase … lands of inheritance …to be conveyed unto Edward Burt, his heirs and assigned subject to and charged and for ever chargeable with the laying out furnishings and procuring yearly on the first day of August for ever the following particulars that is to say, five pounds for a badge of silver weighing about twelve ounces and representing Liberty to be rowed for by six young watermen according to my custom, eighteen shillings for cloth for a livery whereon the said badge is to be put, one pound one shilling for making up the said livery and buttons and appurtenances to it and thirty shillings to the Clerk of Watermens Hall which I would have to be continued for every year in commemoration of His Majesty King George’s happy accession to the British throne.”

Mr. Burt was put off by the notion of managing the race in perpetuity, and instead entered into a deed with the executors of Doggett's will who arranged to pay £300 to the Fishmonger's Company. This effectively moved the trusteeship of the event to the Fishmonger's Company (established in 1272!) which has arranged and funded the race ever since.

Get a look at Doggett's past and future. Watch Liquid History: Doggett's Coat and Badge Race on Vimeo.